From the 1960s onwards, Les Lalanne captivated a whole generation and soon had a cult following among notable private collectors around the world who either bought their works or even commissioned them bespoke projects. Fashion luminaries such as Coco Chanel, Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé, Karl Lagerfeld, Valentino and more recently Marc Jacobs, John Galliano, Tom Ford and François Pinault are some of the Lalanne’s biggest collecting fans. For the past 50 years the eccentric French husband-and-wife sculptors – Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne called Les Lalanne have cast all forms of flora and fauna in iron and bronze.

Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne in Tourterelle, 1997

Known individually and collectively since the 1960s, Les Lalanne developed a style that defines inventive, poetic and surrealist sculpture. Having rediscovered the Renaissance art of casting forms from life, then employing contemporary electro-plating techniques, Claude Lalanne achieves a delicacy and sensitivity in her work unparalleled in cast bronze. François-Xavier Lalanne similarly found inspiration for his works in nature. In his words, “The animal world constitutes the richest and most varied forms on the planet.” His subjects consist of a menagerie of animals, stylised forms oftentimes married with functionality. His works achieve streamlined elegance in their profound simplicity.

The latest and largest gathering of Lalannes was the retrospective at Le Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 2010 in Paris.

The pair’s work represents a surrealist zoo of everyday objects. François-Xavier—who passed away six years ago at the age of 81—produced realistic bronze sheep covered in fluffy sheepskin, which famously graced the library of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé (reflected in wall mirrors framed by lily vines cast by Claude).

In 2008, the year of François-Xavier’s death, one of his sheep stools sold for more than double the estimate, at $158,50. On December 2012 in New York, a pair of Lalanne sheep stool sculptures sell for $542,500. And in December 2011, a group of ten sheep, “Mouton de Pierre” designed circa 1979, sold for $7.5 million at Christie’s New York.

Realistic bronze sheep covered in fluffy sheepskin famously graced the library of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé.

Claude and her late husband, who worked closely since their first joint exhibition in 1964, have long been regarded as a single entity by the public, despite rarely actually collaborating on a piece of work. Both sought to demystify the sacred art of sculpture and create works with a function, that invite us to touch them, sit on them, sleep inside them and at times, even eat them.

All the animals keep a quirky little secret, which makes them as much artifacts as art objects. Backs and bellies reveal unlikely functions, as a secret drawer opens from the chest of a minotaur or seating is glimpsed under the hairy coats of a herd of camels.

Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne. Photo by Pierre Boulat/Cosmos

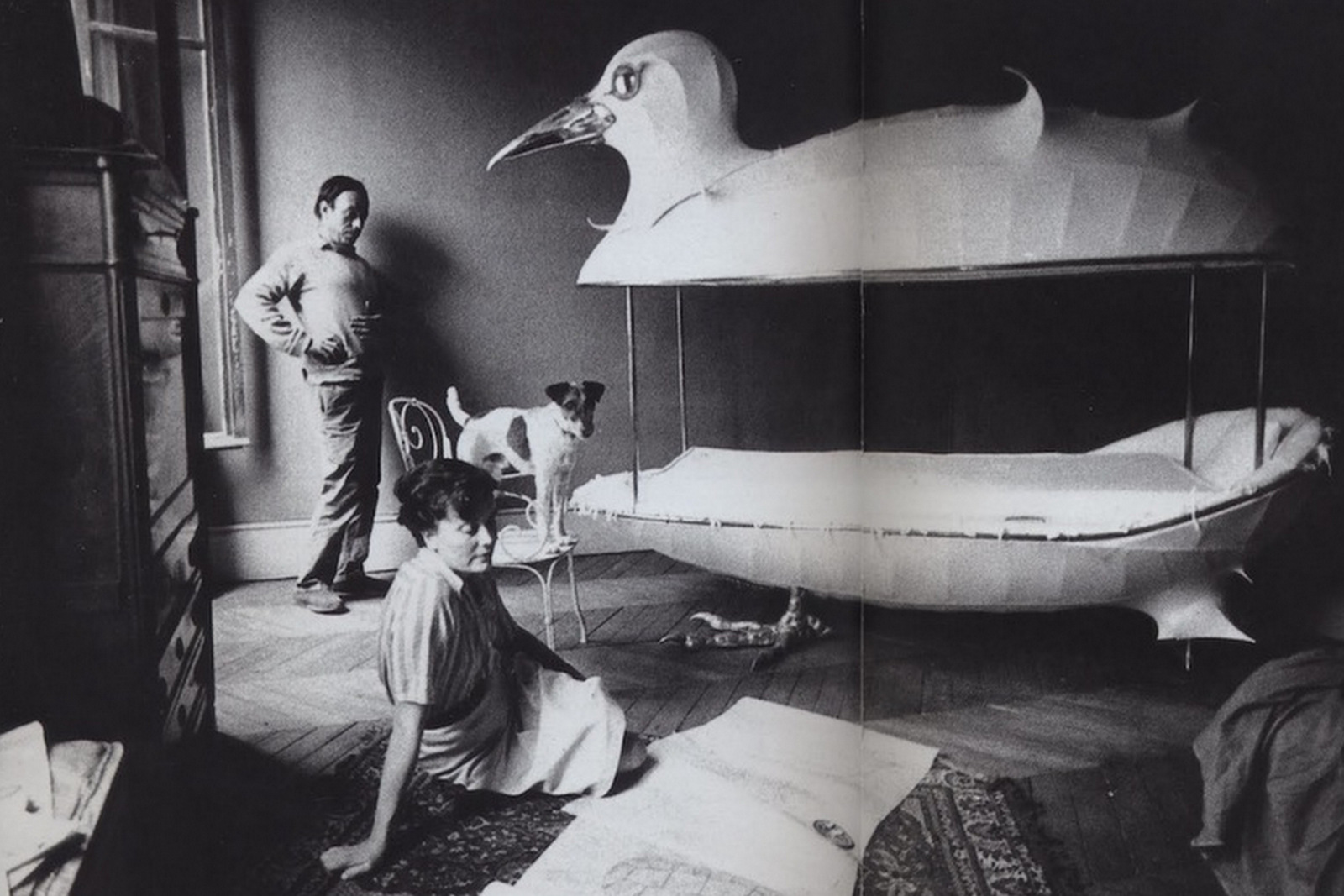

While François-Xavier’s mischievous beasts – like the baboon with fire literally in its belly, because the body is a chimney above a carved-out fireplace and the hippopotamus that opens to become a bathtub – are weighty, fluid forms constructed using moulding and electroplating techniques, Claude’s work tends to be more intricate. Expect delicate mouldings of bodies, apples and cabbages, as well as jewellery, furniture and tableware.

Baboon that doubles as a fireplace, François-Xavier’s Lalanne, Paul Kasmin Gallery

François-Xavier Lalanne, Hippopotame I – hippopotamus that opens to become a bathtub, 1968-1969, polyester resin, copper, and iron, 179.1 x 281.3 x 85.7 cm

Defining the differing styles of the two, the American architect Mr. Marino says that “his art was derived from animal gestures while she has great powers of observation.”

Pomme de Ben, 2007/2008 – Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne

“Choupatte Moyen (Tres Grand),” Cabbage, Claude Lalanne 2008, Galvano and Bronze

Maquette des couverts réalisés for Alexandre Iolas by Claude Lalanne, 1966. Photo by Alexandre Baillache

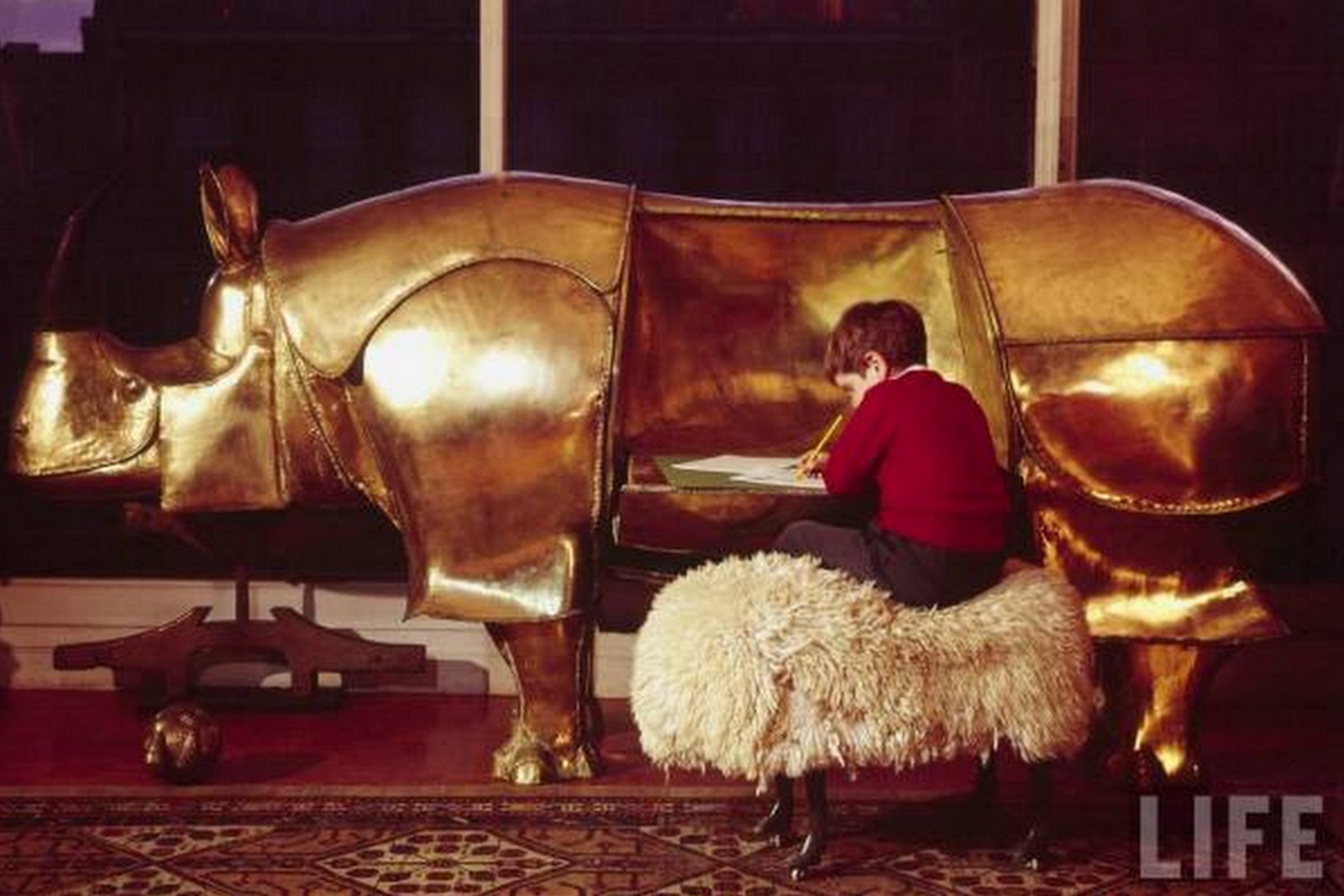

François-Xavier began studying sculpture, drawing and painting at Académie Julian in Paris at age 18. He met Claude during his first gallery show in 1952. Twelve years later, their first collaborative exhibit included his famed Rhinocrétaire desk whose metal hide opens to become a desk is the kind of thing no gazillionaire Bond villain should be without and Claude’s crinkly turquoise cabbage, which like the Russian witch Baba Yaga’s house, stands on chicken legs. Indeed, François-Xavier smooth-skinned, round-edged creatures, have a geometric simplicity redolent of the 1960s-era when a revamped version of modernist design and the English super-spy were born.

Rhinocrétaire desk by François-Xavier Lalanne

At first the art world considered the work too practical—an opinion that the couple countered. “To be honest,” Claude later mentioned in an interview, “a desk in the shape of a rhinoceros is not that practical. If you need a desk, you don’t immediately think of buying a life-sized rhinoceros… maybe for Dali, but not ordinary people.”

Ostrich Bar, François-Xavier Lalanne 1966. Dimensions: 120 X 185 cm. Musée national de la céramique, Sèvres

Crocodile Banquette, a gilt-bronze and copper crocodile bench designed by Claude Lalanne in 2008, was sold by Christie’s for $482,500 in December 2009.

Cocodoll, François-Xavier Lalanne, 1964

The couple’s foremost friend and collaborator was Yves Saint Laurent, whose infamous molded metal bustier of 1969 for the model Veruschka pre-dated Madonna’s conical bosoms by more than two decades. The breast plates attached to the flowing chiffon dresses created shock and scandal on the runway.

In 1969, the Lalannes collaborated with Yves Saint Laurent for one of his collections: they designed moulded bronze breastplates and bustiers that served as the bodice of a gown for the model Veruschka.

And New York architect Peter Marino, who has assembled possibly the world’s largest collection of the art, writes that when he commissioned a lily pond in the country, his young daughter said to Claude, “I’d like to be able to skip across the pond on hidden steps that no one could see, so it will seem like I’m walking on water.” Claude responded by designing bronze lotus-leaf pads rising on stems bolted to the tiled floor of the fountain.

It was also Peter Marino who designed the exhibition called “Les Lalanne” at Les Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Les Lalanne, Musee des Arts Decoratifs – 2010. Architect: Peter Marino Architect. Photo © Manolo Yllera. Courtesy Peter Marino Architect 2010

“There are no pieces that don’t hide something,” says Béatrice Salmon, the museum’s director. Her aim was to show the playful waltz between the two artists, both of whom made pieces that touch on the traditions of antiquity, artisanal handwork and the decorative arts.

Les Lalanne, Musee des Arts Decoratifs – 2010. Architect: Peter Marino Architect. Photo © Manolo Yllera. Courtesy Peter Marino Architect 2010

For Mr. Marino, this museum show was a labor of love. “It’s easier to open five Vuitton boutiques than to do the work for a 100-day exhibition,” said the architect, referring to his day job for luxury brands.

Les Lalanne, Musee des Arts Decoratifs – 2010. Architect: Peter Marino Architect. Photo © Manolo Yllera. Courtesy Peter Marino Architect 2010

Today, it is not uncommon to come across Lalanne’s flora-and-fauna pieces of art in the elegant and eclectic homes of serious collectors.

Manhattan home of Reed and Delphine Krakoff, New York. The Claude Lalanne bronze crocodile chair sits next to a chrome-and-Lucite Guy de Rougemont coffee table. designed by Delphine Krakoff. Photography by Sheila Metzner.

The living room features a metal bar made by François-Xavier Lalanne for Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. On one side of the living room, a pair of Lalanne bronzes—a desk in the form of a preening mountain sheep and a ram stool. Carla Fendi Rome Palazzo Home. Architectural Digest

Claude Lalanne alligator chair. Courtesy of Peter Marino Architect.

“They lived and worked together 50 years, were inseparable,” says Kasmin of the couple. “The alligator chairs, that’s her; the hippopotamus bar, him. His pieces tended to be made in a foundry in an edition; her work is more organic, made of bits and pieces.”

Drawing inspiration from flora and fauna, the Lalannes’ sculptures embody an eclectic style that references classical antiquity, surrealism and the Baroque.