The extraordinary work of Alexander McQueen is now accessible to all, thanks to a new V&A exhibition, Savage Beauty (London, SW7; 0800 912 6961; vam.ac.uk) until 2 August 2015

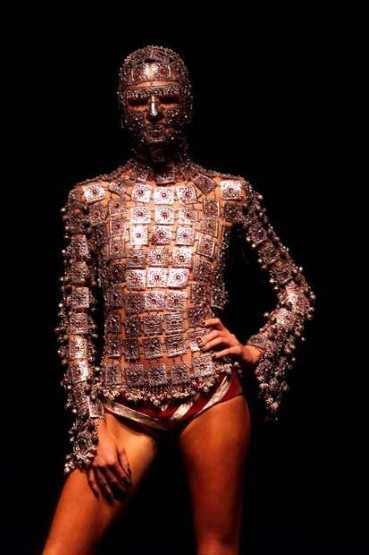

The exhibition brilliantly displays McQueen’s button-pushing, zeitgeist-shaping show clothes in all the bum-revealing glory: the metal body corsets, coats made from hair, Latex-fused skirts that look as though they’ve emerged from some primordial swamp and one particularly ravishing ball-gown which, when he originally showed it on the catwalk, was constructed from real roses, but in the exhibition is formed from silk ones.

Caroline Trentini wearing a silk dress embroidered with fresh flowers from McQueen’s Spring 2007 collection.

The so-called scandalous details of McQueen’s life, gleefully recounted in a recent book, tend to obfuscate the more interesting aspects of his story: his genius and his vision. The latter is a much over-used word in fashion, but McQueen really possessed it. “I try to protect people,” he once told me. “A lot of my clothes are hard-edged, like armour.”

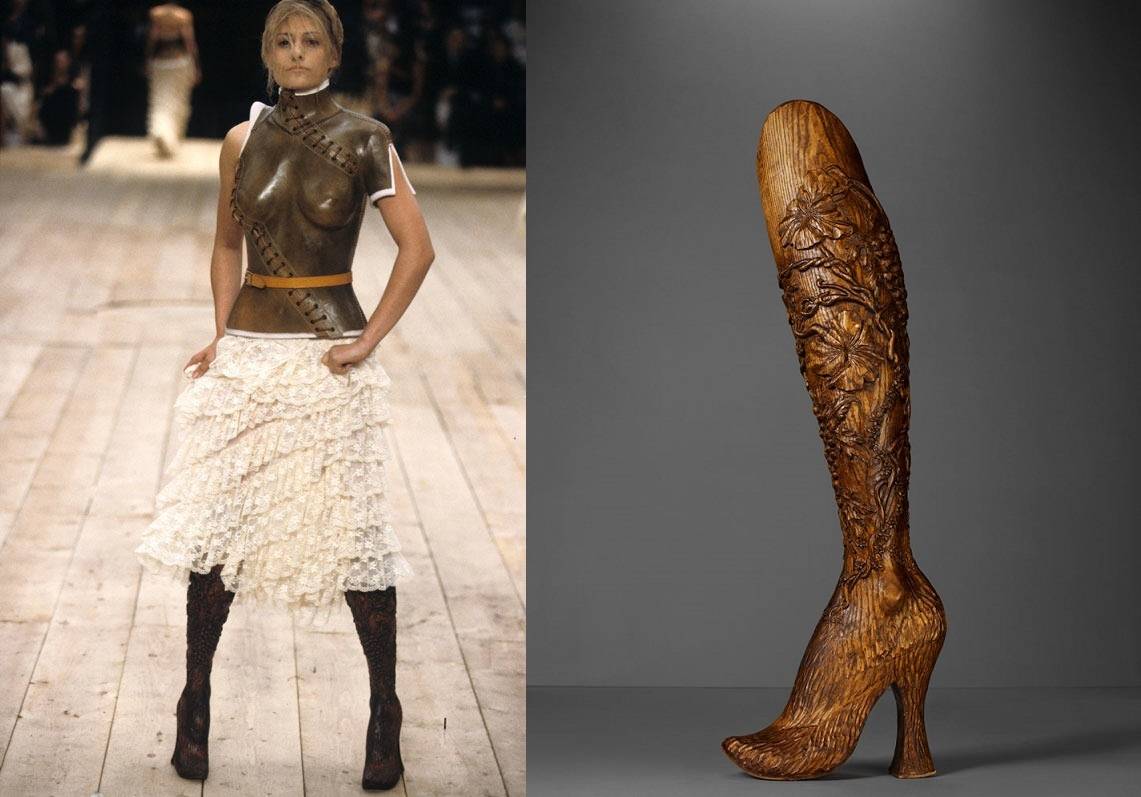

Most fashion shows were (and still are) formulaic, often quite sedate affairs. McQueen’s were unboundaried, part fashion show, part deliciously menacing, immersive theatre. The menace was genuine: you never knew how far McQueen – who loved to shock almost as much as he loved engineering a traditionally tailored suit – would push. Models were caged, spray-painted live on stage until their dresses resembled a Jackson Pollock. They were trapped in glass boxes with thousand of butterflies, forced to walk in dangerously high shoes that made their feet look like the claws of an alien species of crustacean, encircled in rings of fire. Their mouths were winched open with silver jewellery that looked like tiny spears, their eyeballs veiled behind white contact lenses that made them look like automata. McQueen’s vision of beauty was never orthodox; he worked with fat models and amputees.

McQueen was known throughout his career as a fashion maverick, fusing creative spark with skilled craftsmanship. For spring/summer 2010, he drew on wide-ranging influences, including Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Picture: AFP

From Hieronymous Bosch to Dante, he took his audiences deep into dark worlds teeming with haunted creatures. One especially choreographed show with exquisitely exhausted-looking models wilting in one another’s arms, was inspired by marathon dances from They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, the 1969 film about The Great Depression. He demanded as much from his audiences as from his models, but the transaction was mutually beneficial. “Often, designers try to ‘pay’ us in clothes,” says O’Connor. “But he paid us in money, even at the start. That was significant. It was a token of his professional respect.”

The spring/summer 2004 show was the hit of the season; based on the 1969 film ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’, with models duetting down the catwalk for a dance marathon

Although undoubtedly part of the poetry, the fact that these intricately conceived spectacles were only ever witnessed by a few hundred journalists, friends and retailers always struck me as a waste. There are fragments of footage of them in this show, their graininess a poignant, low-res reminder of their ephemeral nature. Thanks to this exhibition, however, a much wider audience will finally understand what made his work so extraordinary.