It may be hard to imagine now, but in the decades after the kaleidoscope was invented in 1816, it become one of the “must have” gadgets of 19th century Britain. A person could hardly walk down a street in Victorian London without seeing someone staring into kaleidoscope and walking into walls from being so immersed in the new invention. This new mobile device that was creating illusions with mirrors as the tube rotated became an adult obsession of Victorian England.

The man who invented the kaleidoscope 200 years ago has almost “vanished from history”, however Dr Peter Reid, from the university’s school of Physics and Astronomy in Edinburgh says it’s time Scots inventor Sir David Brewster was reclaimed. “He was a man who was actually known and highly regarded in the scientific community at the time for a whole range of things he did. People in his time would have said, ‘oh that’s a Brewster invention.”

Inner Cigar Box Label from the Early 1900s with a Portrait of Brewster. Image Courtesy of Kevin Kohler.

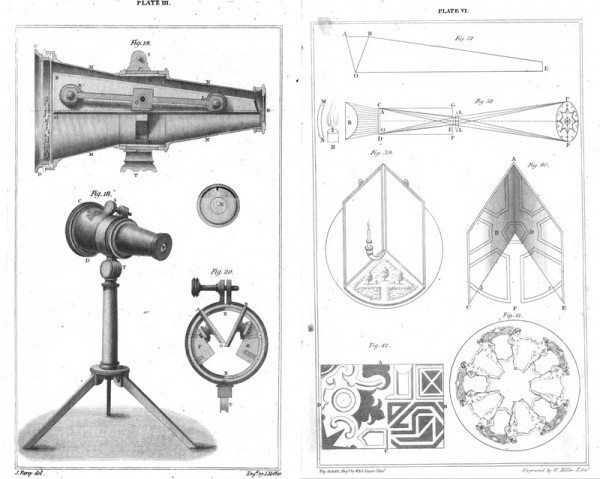

The early kaleidoscopes were handheld and made from a range of materials, such as brass with embellishments of leather or wood or tin. The base of the tube was typically filled with broken pieces of glass, ribbons, or other small trinkets. Two years before the kaleidoscope was invented, Brewster was conducting experiments on “the polarisation of light by successive reflections between plates of glass.” And it was while experimenting with the relationship between optics, light, and mirrors that he began to notice that when the reflectors were inclined toward each other, they created circular patterns as the image multiplied across the surfaces.

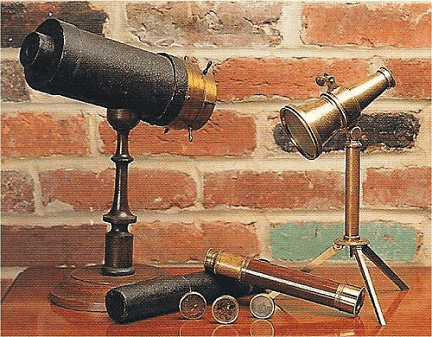

Kaleidoscopes of Sir David Brewster and Charles G Bush. Photograph Courtesy of John Woodin.

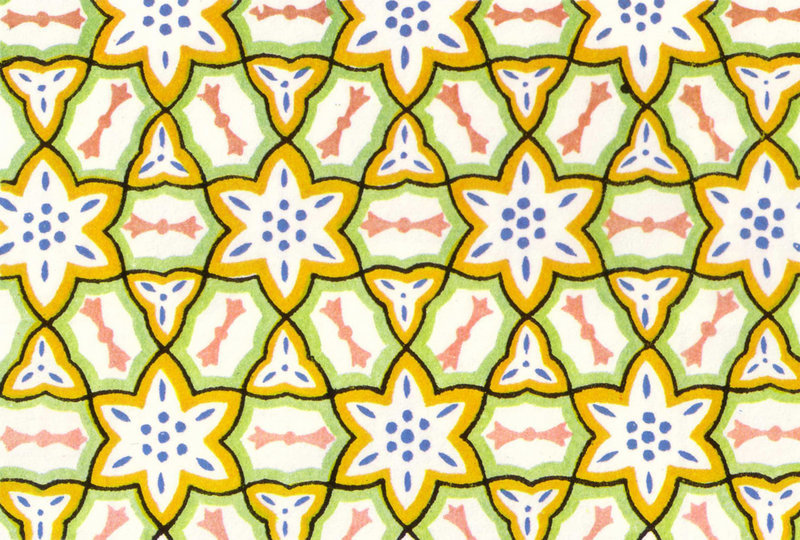

In addition to scientific and industrial value, the kaleidoscope that captured the 19th century also held aesthetic value due to visual symmetrical beauty. The nearly-infinite symmetrical varieties created by the kaleidoscope, were used for patterns on carpets, china, paper, floor-cloths, and other fabrics.

A Kaleidoscope-esq Pattern for Wallpaper, 1856. From The Grammar of Ornament (1856) by Owen Jones.

An 1819 issue of New Monthly Magazine, in listing the “most important inventions and discoveries of our times”—ranging from uses of combustible gas for illumination, uses of the newly discovered metal cadmium, advances in infrastructure and timekeeping, among others—ends its article by stating, “Lastly, no invention, perhaps, ever excited more general attention among all classes of people, than the kaleidoscope.”

Royal Fans. Queen Victoria was Said to be Fascinated by the Kaleidoscope. Photograph Courtesy of University of Edinburgh.

R. S. Dement – a philosopher and playwright in Victorian America, recalled the moment he discovered what was inside a kaleidoscope as a child. He was originally fascinated by the reflections of colours bouncing around in various symmetries; but upon taking the kaleidoscope apart, he discovered nothing but “numerous pieces of coloured glass, without symmetry, unsightly in themselves, have no connection with each other and but very trifling value.” He felt betrayed, “deceived into believing that what he saw was at least the shadow of something real and beautiful, when in truth it was only a delusion.”

His reflections, however, match nearly the description of the inside of a kaleidoscope written in a magazine article in an 1818 issue of Literary Panorama, at the beginning of the kaleidoscope’s rise to popularity. The article states: Many people of the era argued that giving attention to the patterns built from such scraps was a waste of time. This was especially pronounced, they argued, when true beauty was all around. All a kaleidoscope viewer had to do was put down the instrument of false beauty and look up at real beauty in nature.

Illustrations from Brewster’s A Treatise on the Kaleidoscopes, 1819. Photograph Courtesy of Hathi Trust.

Devices for seeing had a particular position in 19th century Britain. At this time, optical objects like the kaleidoscope, the telescope, the periscope, the microscope, and emerging “philosophical toys” designed for use by the broad public to better understand scientific principals created certain ways of seeing the world that had been impossible until this point.

Another popular 19th Century Optical Device, a Phenakistoscope, in Action. This adorably formal couple would flirt, over and over and over again.

Sir David Brewster patented his invention which would have guaranteed his exclusive rights to the kaleidoscope production however, kaleidoscopes were being “pirated” and Brewster seemed to have little recourse to such piracy as his patent was not correctly laid out.

There’s an estimate that the inventor could have made £100,000 which is between £10 million to £20 million today out of his invention when, at the time, £700 a year was considered a lot of money.

Kaleidoskop Bewegung

The “kaleidoscope mania” lasted for several decades. By last half of the 19th century, there wasn’t a single kaleidoscope seen on the streets of London. By this time, kaleidoscopes had all gone indoors becoming novelties and conversation pieces in the home. They were less mobile than they were portable within the owner’s house. Essentially, the kaleidoscope had been “domesticated.” By World War II, the kaleidoscope was securely in the realm of children—no longer existing as a centrepiece for adult conversation—and once again was sold without a stand. Instead, they were made of cheap materials and sold among erector sets and Kewpie dolls. While it is obvious that the kaleidoscope was much more than a “mere toy” for early 19th century Britain, articles and editorial pieces that disparaged the kaleidoscope almost always refer to it as a “mere toy” or a “child’s plaything”. Of course, a glance around the streets of London would tell you otherwise.

Found Photo, Three Girls with Kaleidoscopes , mid-1960s. Courtesy of Whitewall Buick.

When the kaleidoscope did emerge, it did so out in public as it required light to function adequately, and thus people took it outdoors to get the best effect. The kaleidoscope also served as a status symbol. No two kaleidoscopes were identical as each varied in some way due to the different elements included at the base of the tube. The kaleidoscope thrived because of its ability to provide variance; people could not wait to see what beautiful pattern would come next.

Artists Construct Giant Kaleidoscope Inside Japanese Shipping Container

Two centuries after the kaleidoscope was invented by Scottish physicist Sir David Brewster in 1816, designers are giving the classic design a run for its money.

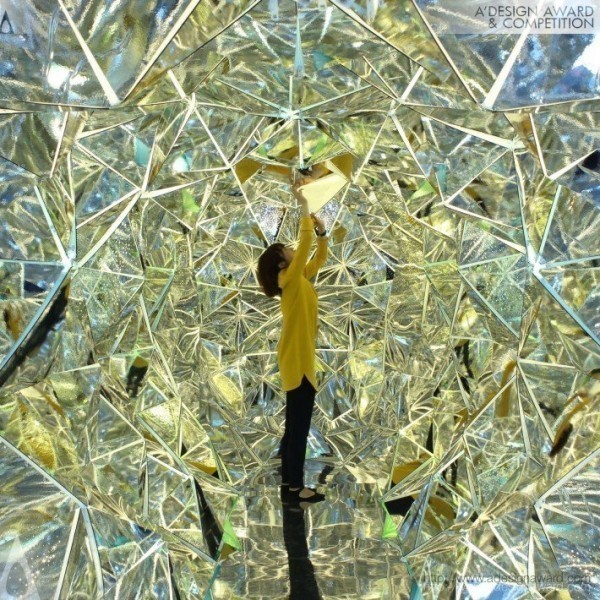

Designers Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki constructed a life-sized mirrored polyhedron installation inside of an industrial shipping container in Japan transforming the space as used in Japanese traditional housing. At work on their origami inspired zipper technology since 2007, the two Japanese practitioners have been high hopes for its future usage as an architectural material for soft, light and moving architecture. The architecture they intend to create should be soft, light and moving and not hard, heavy and fixed.

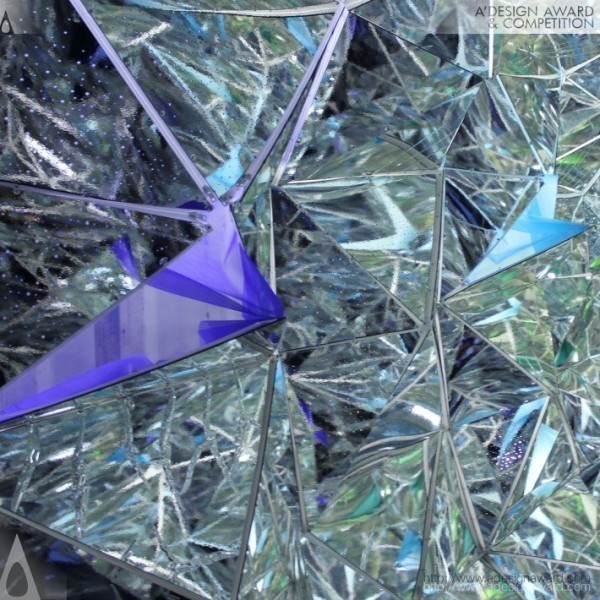

Wink by Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki. Photograph Courtesy of Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki.

They believe that their concept is suitable for the architecture of the 21st century with a Zipper being a possibility for a new technology. The most effective way to exhibit the work in a container, relies on assembling which was completed in 4 hours, taking apart and moving simply and quickly with zipper being very effective for that. To build the zipper architecture a thin and light material was demanded therefore, artists referred to origami, which is a traditional game in Japan that can be made both light and strong only by folding. In other words, this polyhedron is built by folding one plane of 15m x 8m into the 40ft container (width 2200mm x depth 10000mm x height 2200mm).

Entitled Wink, the installation, which premiered at Kobe Biennale’s Art Container Contest is their third prototype. It is made up of 1,100 panels of only two separate triangular shapes, using digital 3D modelling studios Rhino and Grasshopper. Thanks to Wink’s folded nature and the additional use of zippers and cloth, the interior can easily change shape just by adjusting the length of the wires that suspend it.

Wink by Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki. Photograph Courtesy of Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki.

This amazing installation is not only an artwork but also the first ‘Zipper Architecture’ in the world. This ‘space kaleidoscope’ can change by the movement of a person and in the container therefore, all of the panels are connected by zippers of which some can be opened and closed like a window. Visitors were free to unzip it as they navigated the space as well! Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki believe this idea could solve global environmental problems, because it is easy to exchange only a part with a zipper. As the team has also managed to connect hard panels such as glass using their designs, keep an eye out for zippable-windows in the very near future.

Wink by Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki. Photograph Courtesy of Masakazu Shirane and Saya Miyazaki.

Flatiron Holiday Installation: Nova by SOFTlab

At the foot of New York’s soaring Flatiron building, local design studio SOFTlab had built an aluminium pavilion that reflected and revealed kaleidoscopic views of the surrounding cityscape ‘Nova’. Nova by SOFTlab was selected as the winning proposal for the second annual Flatiron Public Plaza Holiday Design Competition held by the Flatiron/ 23rd Street Partnership Business Improvement District (BID) and Van Alen Institute.

SOFTlab’s Nova Pavilion. Photograph Courtesy of Alan Tansey.

SOFTlab’s Nova offered an unusual and playful perspective of the landmarks and street life surrounding the plaza that were visually stimulating and interactive as it compelled passers-by to enter the structure and gaze onto Flatiron’s iconic landmarks.

In Nova, the placement of viewing cones, was arranged to represent a centralised North Star for the Flatiron District, with each scope pointing to a different distinct landmark. Nova acted as an observatory for the “constellation” of iconic sites in the neighbourhood: the Flatiron Building, Met Life Tower clock tower, Empire State Building, and surrounding landmarks.

SOFTlab’s Nova Pavilion. Photograph Courtesy of Alan Tansey.

“Using a mix of optical materials, SOFTlab’s design created a ‘human scale kaleidoscope’, remixing the surrounding iconic buildings with colour, light, and the reflections of pedestrians,” said Michael Szivos, Founder and Principal at SOFTlab. “Although our design reads as an iconic and festive figure from above, the experience at the pedestrian level was very different. The exterior gave way to a crystal-like, mirror-surfaced interior that looked different from all sides.”

SOFTlab’s Nova Pavilion. Photograph Courtesy of the Van Alen Institute.

The pavilion was made of a modular system in collaboration with Arup. On the outside a lightweight aluminium shell gained its strength through a cell-like structure. Each unit was made of two dimensional panels that were attached together to form a three-dimensional cell. These pieces were then joined to create a stable dome in its centre, with each scope acting as an arch. The synthesis between the dichroic film and the mirror-finished aluminium panels turned each viewing cone into a pedestrian scale kaleidoscope.

SOFTlab’s Nova Pavilion. Photograph Courtesy of © 3M

Sponsored by the Flatiron/ 23rd Street Partnership, Nova and the accompanying programming “23 Days of Flatiron Cheer” was also made possible with generous support from Presenting Sponsors Tiffany & Co. and Meringoff Properties, Contributing Sponsors Grey Group and Macmillan.

SOFTlab’s Nova Pavilion. Photograph Courtesy of the the Van Alen Institute