When news broke on Thursday morning 31st Mar 2016 that architect Zaha Hadid had died, she was quickly mourned by a trio of her peers: Frank Gehry and Joseph Giovannini sat together over breakfast and called Robert A. M. Stern to have a group cry. “We just loved her,” Gehry tells TIME.

Architects Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry. Photograph Courtesy of Seth Browarnik, Nathan Valentine, Rodrigo Gaya, Ryan Troy World Red Eye

Gehry initially helped Hadid obtain her first major commission, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany. “She did an extraordinary job with it,” Gehry recalls. “Everybody was impressed, and she took off.” According to Gehry, one of Hadid’s great strengths was that she “created a language that’s unique to her,” the architect says. “I suppose it’ll be copied, but never the way she did it,” he adds.

Vitra Fire Station in Germany by Zaha Hadid Architects. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

A woman in the most masculine of the arts, Zaha Hadid polarises opinion like no other – and far beyond the realm of architecture, yet here is a person who has won every top award in her discipline pushing the formal and technical boundaries of building. Now Hadid is one of the world’s most respected architects but for decades she was known as a ‘paper architect’ because of her inability to get designs built.

Zaha Hadid. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid.

As the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, in 2004, Hadid was an outspoken critic of gender inequality in architecture. In 2013, she told The Observer that misogyny was still alive and well in the profession of which she was a leader. “It is a very tough industry and it is male-dominated, not just in architectural practices, but the developers and the builders too,” she said. “Society has not been set up in a way that allows women to go back to work after taking time off.”

Zaha Hadid by Elena Boccoli. Photograph Courtesy of Elena Boccoli.

Painting formed a critical part of Hadid’s early career as the design tool that allowed her the intense experimentation in both form and movement – leading to the development of a new language in architecture. To her painting was always a critique of what was available as 3D design software did not yet exist.

Zaha Hadid’s Four Decades of Breaking the Box by Aaron Betsky. Tektonik Painting by Malevich.

Computer modelling software arrived in Hadid’s office in 1990. Before that, the office struggled modelling her multi-perspective warped designs, recalls Patrik Schumacher, a company director and senior designer at Zaha Hadid Architects. Traditionally, architects draw sections and plans by hand and with drafting tools using geometric shapes like circles, triangles, squares, rectangles. Schumacher remembers that in an effort to distort the shapes, they used the sizing tool on the photocopier by placing drawings on the glass diagonally and instructing the machine to expand or shrink them; in stretching and squeezing the image, the machine warped the lines.

Vision for Madrid, Spain, 1992. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

For years, Hadid submitted abstract drawings and paintings to convey her bold ideas, because, as she would explain with absolute conviction to all those doubtful clients, abstraction was the best way to capture multiple perspectives in two dimensions, and to bring them together in a “distortion field.”

For her, abstraction opened the possibility of unfettered invention. “I wanted to capture a line, and the way a line changes and distorts when you try to follow it through a building, as it passes through regions of light and shadow. You know when you look through a building from a window on the outside, and the line you are following is distorted by the space? That was what I was trying to see with my paintings and my whooshings.”

Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich, Switzerland. Photograph Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

A bright explosion of Russian works pierces through the contemporary works of Zaha Hadid in a dynamic black and white design. The dialogue of these works constantly shifts and realigns as one moves through the space focusing on four themes: Abstraction, Distortion, Fragmentation, and Floatation.

The exteriors of her buildings are shaped by the movement inside and around them, rather than by some predetermined notion of external form. “I’ve always been interested in how our movement through space affects architecture. As in the frames of a film: not seeing the world from one particular angle, but having a more complex view. We view the world from so many perspectives – never from one single viewpoint – our perception is never fixed. This movement through space is very critical in all buildings – which also impact our perception of time and the relationship we establish with our built environment. It differs from the pure perception of speed,” Hadid explained.

Mobile Art Chanel Contemporary Art Container by Zaha Hadid Architects. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

According to Hadid, architecture does not follow fashion, political or economic cycles – it follows the inherent logic of cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Does fashion then follow architecture? From what we have seen on the runways, fashion designers were not immune to the so-called Zaha Hadid syndrome, consisting in indirectly referencing architectural elements. Victoria Beckham‘s geometric form for example that linked her most to Hadid was the architectural triangle employed in the design of Guangzhou Opera House.

Guangzhou Opera House by Zaha Hadid Architects and Victoria Beckham’s Triangle-Appliquéd Silk and Wool-Blend Crepe Shirt.

One can surely detect a watermark in Hadid’s futuristic smoothness. Certain themes carry through her use of materials like glass, steel and concrete, her corridors often trace flowing arabesque shapes, while roof struts make sharp Z-shaped angles. Hadid favoured column-free spaces, sculptural interiors and asymmetric façades.

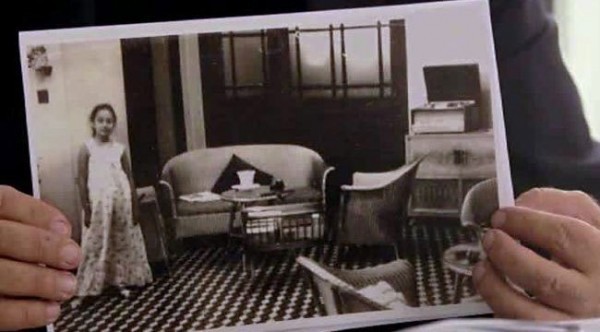

Born into a wealthy family in Baghdad, in 1950, Hadid grew up at a time when Iraq’s capital was a cosmopolitan, progressive city, full of cultural experiments and new ideas. Her parents, both from distinguished families, had a large house that had been built in the nineteen-thirties. Hadid decided to be an architect at the age of 10.

Zaha Hadid as a Child in Baghdad. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid.

“The style of the furniture in my room was angular and modernist. I remember as a child really wanting to know why these things looked different. Why is this sofa different from an ordinary sofa?” She had an asymmetric mirror. “I was thrilled by the mirror,” she once told the London Times. “It started my love of asymmetry.” There were some traditional furnishings, including Persian carpets with intricate patterns. Hadid explained, “You have to understand there is no figurative art in Arabic tradition—it is all decorative patterns that come from geometric design. So, of course, those things influence you.”

‘Never failing to provoke or fascinate’: Zaha Hadid in the auditorium of her Guangzhou opera house. Photograph Courtesy of Dan Chung for the Observer.

Despite Britain’s opposition to her buildings, Hadid lived and worked in London for more than a quarter of a century. “The British still don’t look forward enough, but London is the most amazing city, it has everything, including an engineering tradition that goes right back to the Victorian era.” In retrospect, Hadid thought that people weren’t ready for her work. It was just too exuberant, too different. “People did not believe in the fantastic. They thought it was impossible to build the kind of spaces we were designing.”

Queen Elizabeth II meets Dame Zaha Hadid, July 27 2012. Photograph Courtesy of Jan Kruger, Getty Images Europe.

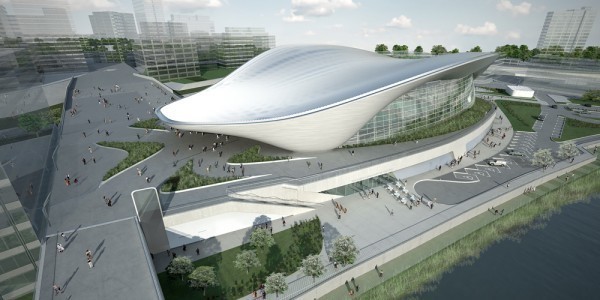

The truth is that London had been both cruel and kind to Hadid. For decades she despaired of ever getting anything built. Projects fell by the wayside at the last minute. As recently as 2008, Hadid said “I don’t know if I’ll ever do a big project in London.” And yet, at this point, she was already half-way through the eight years spent working on the Aquatics Centre.

London Aquatics Centre by Zaha Hadid Architects. Photograph Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

For an Arab female to be one of the most highly regarded architects in the world is no mean achievement. Londoners should have been flattered that Hadid had chosen this city as her home despite failing to use her considerable skills and her feisty, flamboyant and freakish talent here.

Zaha Hadid in her London office, circa 1985. Photograph Courtesy of Christopher Pillitz, Getty Images.

Hadid never had her own office; she would sit right in the middle of her studio for many years. Arriving late in the morning, she would sketch for an hour or so, and then begin asking to see projects, and her employees would feed her plans and renderings. In recent years, however, she had let her business partner Patrik Schumacher run the office, while she often worked and took meetings at her home, a five-minute walk through the narrow streets.

Zaha Hadid Reviewing the Finished Product at her London office. Photograph Courtesy of Dan Medhurst.

Hadid’s Clerkenwell office is a converted 1870s school with a Victorian sign saying ‘Girls, Infants’. Isn’t that ironic? For years, Hadid was treated as the infantile girl of architecture. Nothing got built, despite her winning competition after competition, notably in 1995 for the Cardiff Bay Opera House, only for her project to be replaced by the Cardiff Millennium Centre. For years she attacked the male architectural establishment in Britain that, she said, stopped her works getting built: the ‘old boys’ network’, the ‘brotherhood’ that met in gentlemen’s clubs and had all the big jobs sewn up. After the Cardiff debacle, Hadid contemplated giving up architecture altogether.

Zaha Hadid’s Office in Clerkenwell, London.

It is impossible to escape the notion of Hadid as workaholic. She had no children and no partner who was ever spoken of. “I don’t regret it,” she said. “It would have been nice to, but I’ve always been too hectic. I think you should only have children if you can give them time. If I’d stayed in the Middle East, I could have done it. The family relationships there make it easier to look after children.”

Zaha Hadid at Home in her Clerkenwell Penthouse. Photograph Courtesy of Alberto Heras.

Hadid owned the top floor of a five-story loft building, where she lived in a penthouse for two-and-a-half years. It was shoes off at her apartment, where the walls, floor and even the AstroTurf that carpeted her roof terrace were all pure white with black metal-framed windows. Her space could also be described extremely, dauntingly, hard. There were no carpets, curtains, cushions or upholstery of any kind. Her furniture consisted of slippery amorphous shapes made of reinforced fibreglass and painted with car paint.

Zaha Hadid in an Elke Walter Coat at Home in her Clerkenwell Penthouse. Photograph Courtesy of Mark C O’ Flaherty.

Certainly, Hadid’s megapod of a penthouse was a chintz-free zone; the clutter phobic flat did represent her uncompromising hard persona straight out of central casting. Hadid’s white space was filled with furniture and paintings of her projects in different media.

There were no books, no CDs and perilously little sign of human occupation. A stalactite table in her lounge positioned towards the terrace windows was full of Scandinavian glass vases. Her glacier sofa formed a part of the Z-Scape line.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

A digital drawing of Malevich’s Tektonik served as a backdrop setting allowing the Aqua table to take a centre stage. Her chairs were from Rifatta Bella by William Sawaya. To the left you can see the Glacier couch designed by her. The pictures on the wall were from her various projects.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

Here’s another perspective of her Aqua table filled with her objects. In the background, you see the series of her paintings which she presented at an exhibition in Berlin.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

Zaha described herself as a gypsy, of no fixed abode with memories in her childhood home. She was inspired by the revolutionary Russian artist El Lissitzky whose works she hang on her walls. Then there was a multitude of portraits, pieces of furniture and objects, shapes that defined the space, marking out her own new avant-garde persona.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Photograph Courtesy of Davide Pizzigoni.

Her penthouse in Clerkenwell could as well have been her own gallery. One could easily imagine Hadid as the Queen of Hearts screaming, “Off with their heads!” She was an amazing monster and uncompromising dictator of her wonderland, and one of the world’s great architects. TIME magazine named her the world’s top thinker in its 2010 list of influential people. This really was her moment. After being dismissed as a fantasist whose building designs were pie in the sky she was finally seeing her visions realised.

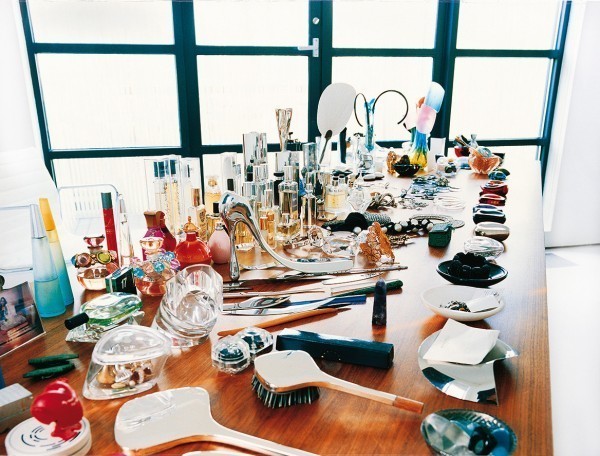

Hadid was not a collector of the works of others, unless you counted her clothes which took up a huge closet. Apart from its contents, her living space was surprisingly conventional. “It was not my project,” she once said. A dressing table in her bedroom could easily resemble a city of miniature combs, fragrances and jewellery.

Zaha Hadid’s Dressing Table in her Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

Hadid had dedicated a small room in her apartment to the collection of Murano glass, vases, plates, balls consisting of different forms and colours. George Nelson colourful Marshmallow Sofa and Pierre Paulin Tongue chair complemented the coloured Murano glass perfectly.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

It was Mrs Prada who made Hadid’s party frocks, and her closet was packed with Miyake, Gigli and Miu Miu. There was more to the architect Dame Zaha Hadid than building design. “I was always interested in clothes,” Hadid explained, admitting she hasn’t thrown anything away for 30 years. Even a spectacular Issey Miyake pleated coat that her housekeeper accidentally ironed flat is now deployed as a poolside cover. Much of her vast collection was kept in concealed cupboards in her apartment.

“I’ve been too daring for my own.. un-benefit”, said Hadid. When criticised she would just say rude things that she wouldn’t repeat in public. When it came to fashion, “I’ve always had an interest in funny outfits. They’re not daring in the sense that they’re transparent or too short or low, just unconventional. I used to kind of wrap myself with things. In those days it looked a little bit odd. Then I discovered Japanese designers like Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto who did everything I wanted to do. They were asymmetrical, quite theatrical and very beautiful, tailored, calm, black pieces. I’ve been wearing these things since the ’80s. My personal style signifiers are black capes, particularly ones by Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake; their early pieces are stunning. I still wear unconventional clothes, and my behavior is not at all conventional.”

Zaha Hadid. Photograph Courtesy of Virgile Simon Bertrand.

The Stalactite table with lacquered wood and Glacier couch in polyurethane with Z-Scape collection for Sawaya & Moroni were all designed by her.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

“When I come to this floor, all I want is a comfortable bed and a nice bathroom,” explained Hadid. Her bedroom is another attack of snow blindness with its huge white double bed and white blinds. The bed covers in her bedroom were designed for the hotel Puerta de America. In the background Hadid hang the black painting by artist Brian Clarke. In front of the bed was a big flat-screen tv and in the bathroom a huge mirror curved and cut like a land mass.

“The only thing about this flat is there’s no kitchen,” she said. How could Hadid live without a kitchen, one may wonder? “Well it did have one, but I took it away. It was ugly.” Did Hadid ever cook? “No, I used to have someone to cook, but he’s gone now. I go out all the time.”

Zaha Hadid’d Bedroom in her Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

Zaha Hadid’s Clerkenwell Penthouse. Courtesy of Architectural Digest, Spain, May 2008. Photograph by Alberto Heraz.

The area around the fireplace was surrounded by paintings for the Haffenstrasse Development in Dusseldorf, Germany. Among the furniture could spot the prototype of her iconic bag for Louis Vuitton.

Hadid would sometimes lie awake in her white-painted apartment. However, what was going through her head wasn’t the usual insomniac’s litany of anxieties and regrets.

“No, no, I lie awake thinking about buildings. I dream about buildings quite often and I’ve even trained myself to work out plans in my head, not just on paper, or on a computer screen.”