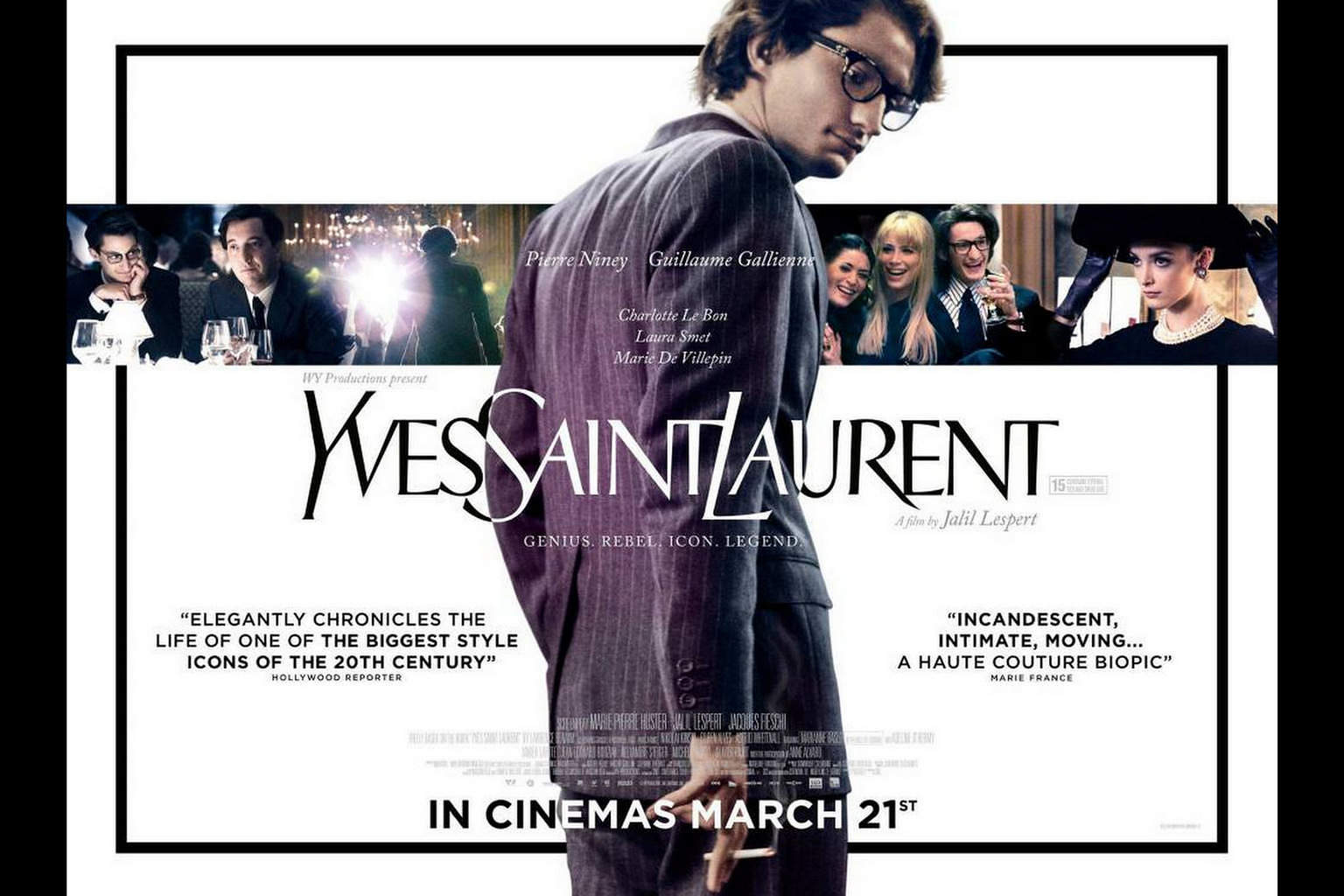

An emotional portrayal of the beginning of the couture house, the newly released film shows Yves Saint Laurent’s tumultuous relationship with Pierre Bergé. It is a celebration of Saint Laurent’s genius but also a painful revelation about his emotional vulnerability and fragile mental health. At times, the likeness of Pierre Niney to Yves Saint Laurent is uncanny, as is the brutal honesty concerning the nature of the relationship between Saint Laurent and Bergé.

The clothes in the film are wonderful, authentic and very beautiful. The interiors in Paris, however, are not. The original Paris apartment and its contents were sold in the famous Christie’s sale, and sadly the ones in the film are in no way comparable to the beautiful, luxurious and glamorous surroundings that Yves Saint Laurent, Bergé and Jacques Grange created which formed the real life film set of this epic, tragic, romance.

With the 1977 launch of Opium, which became the world’s best-selling perfume, Bergé and Saint Laurent were suddenly showered with millions. Practically overnight, the duo were in a position to buy “almost anything,” says Thomas Seydoux, international co-head of the Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art Department.

Opium Fatale. Yves Saint Laurent launched opium perfume for women in 1977.

After Saint Laurent’s death, his and Bergé’s interiors were auctioned at Christie’s in 2009 for an astounding $484 million—the Gray chair alone brought just over $28 million. Despite, or perhaps because of, that dispersal the legend of the apartment will surely continue to grow. As Saint Laurent’s favorite writer, Marcel Proust, once observed, “The only paradise is paradise lost.”

The empire-building entrepreneur believes Saint Laurent, with whom he had a pacs (civil union), would not have approved of his plan to liquidate their collection. But, Bergé says, “I don’t want to think about that.” In a repeat scenario of 80 years ago, when the duplex at 55 Rue de Babylone was first optimistically renovated by the American, the global economy is collapsing. “The purchase of art turned out to be more clever than buying stock,” Bergé reflects. “But that is not important—I did not buy for that reason, and I am not selling for that reason.”

Bergé, for whom the collection lost its significance when Saint Laurent died last June, said he feels neither regret nor nostalgia on parting with the collection. “I am waiting to see how this sale will proceed with calm and with confidence,” he said, adding the scene unfolding in the Grand Palais, which is hosting an auction for the first time, is like a film. In 11 rooms, spreading more than 130,000 square feet, interior architect Nathalie Criniere has created an elaborate setting that includes replica designs of Saint Laurent’s salon and dining room. “I am dazzled. It’s extraordinary,” Bergé said of the overall effect.

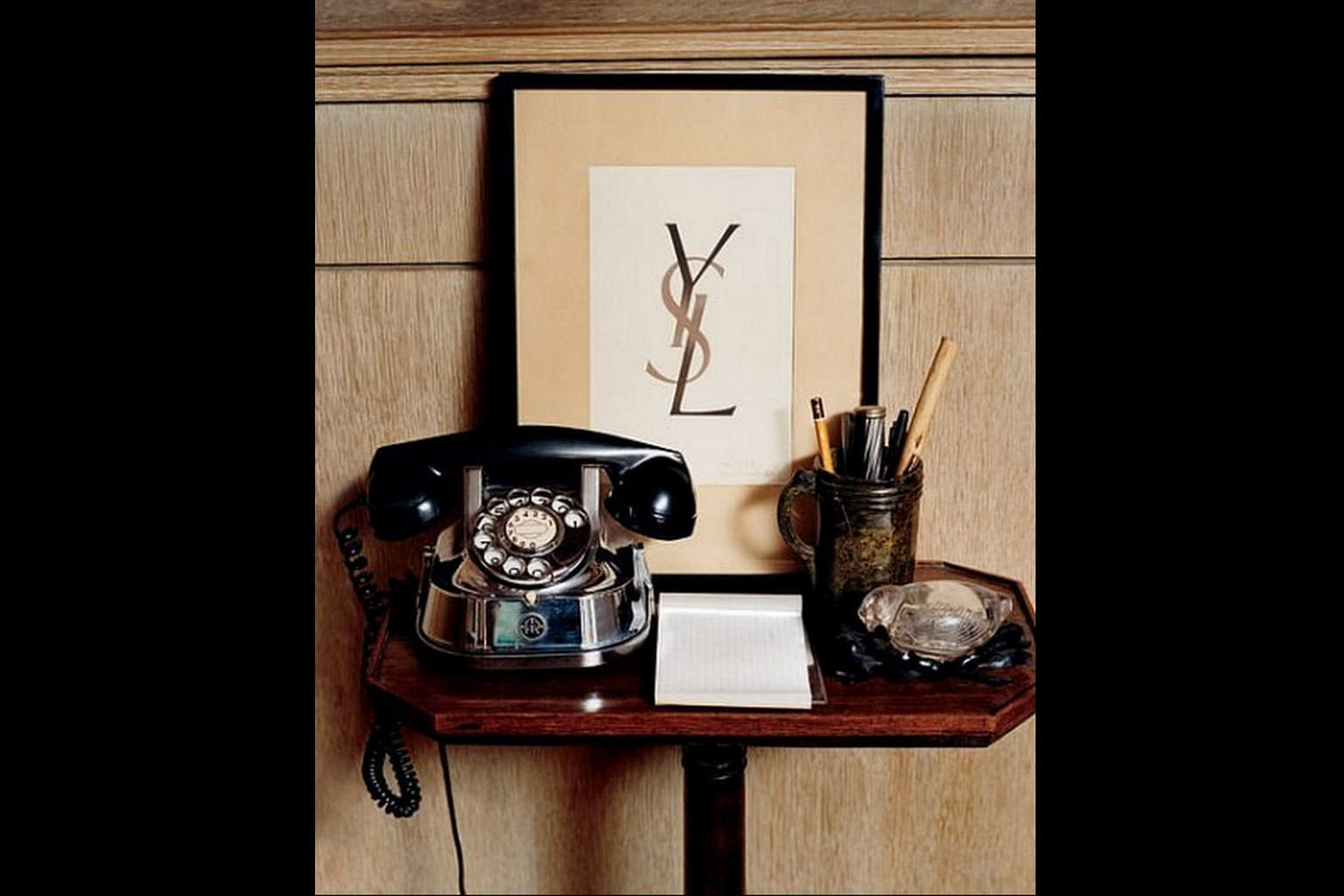

On a telephone table in the library of the Rue de Babylone apartment: the couture house’s original logo, hand-lettered by graphic artist Cassandre, from 1961 (not for sale). The bleached-oak bookcases are by Jacques Grange. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

The book The private life of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé is perhaps one of the best ways to really see this style, and remember it in its true glory before memory and film merge and create their own version of the truth.

Jacques Grange was 21 when he began working for Saint Laurent and Bergé. He helped polish the decor as the apartment’s rooms became densely enriched—by Old Master drawings, a rare Eileen Gray dragon chair, and surrealistic fancies crafted by the prolific Lalannes. The Renaissance bronzes reflected Saint Laurent’s admiration of the art-loving Rothschild clan, and his devotion to Frank echoed his fondness for the irascible arts patron Marie-Laure de Noailles, Frank’s seminal client. Grange learnt from the very best and took this knowledge, of the importance of dialogue, into his work with his clients. Working with Saint Laurent was undoubtedly a wonderful opportunity.

In the library, a cylindrical crystal vase is situated on the François-Xavier Lalanne–designed multi-metal and ovoid Bar YSL. Mondrian’s 1920 Composition No. 1 is displayed above a fireplace. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

“Yves deepened my knowledge of colour, sharpened my perception of it. But I am also amazed by the unbelievable number of objects, pieces of furniture, paintings, tapestries, carpets and drawing and sculpture to come into Yves and Pierre’s hands, which they managed to hang on to, because we are talking about true collectors who collect with a concern for literacy and historical knowledge and also a taste for excellence and for sharing. Their homes seem to be haunted by countless story book characters” – Jacques Grange

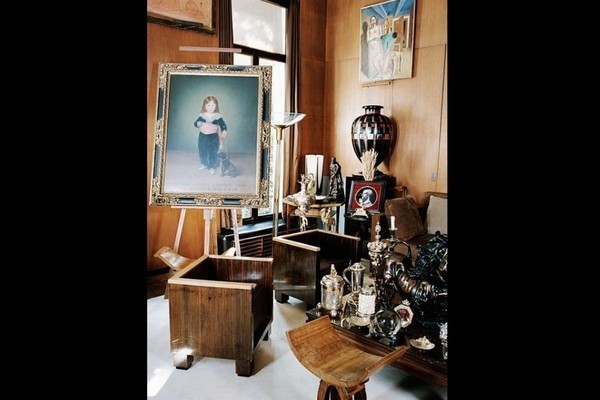

Exhibited on an easel, Francisco Goya’s Portrait of Don Luis Maria de Cistué (1791), which was donated to the Louvre Museum, is surrounded by a pair of cubic French Art Deco chairs and a Pierre Legrain stool, circa 1925. Toward the right is a 1925 Jean Dunand copper-and-enamel vase below a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, 1917–18. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

Exhibited on an easel, Francisco Goya’s Portrait of Don Luis Maria de Cistué (1791), which was donated to the Louvre Museum, is surrounded by a pair of cubic French Art Deco chairs and a Pierre Legrain stool, circa 1925. Toward the right is a 1925 Jean Dunand copper-and-enamel vase below a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, 1917–18. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

With residences in Paris, Manhattan, Marrakech and Tangiers, Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent had this fairy-tale country retreat built not far from Château Gabriel, the late 19th C mansion the fashion power couple purchased in 1980 on an 120-acre estate. After the death of the couturier in 2008, the business mogul sold their storied Paris apartment and the chateau as well as most of their museum-quality art and antiques collection but kept ‘La Datcha’ (the French spelling for the Russian word dacha meaning holiday home). This 19th C flamboyant country cottage was decorated by Jacques Grange. It was built as a multi-purpose living area with a main room and only a small kitchen and powder room. It has no bedrooms. Bergé asked Grange a few years ago to build an outhouse, with a covered walkway, that would be linked to the cabin and that would serve as a sleeping annex containing a guest suite and a master bedroom.

Salon at the Datcha Grange created for Saint Laurent at Chateau Gabriel. Antique stained-glass doors and pine paneling line the multipurpose salon that takes up most of the property’s Russian-style main building, which was created in the 1980s.

In the apartment in Rue de Babylone objects were layered and brought together in a unique juxtaposition. Ancient Greek statues, Modern Masterpieces, Augsburg Silver, Cameos, William Morris tapestries and great works of Modernism all came together creating a very rich and opulent mise en scene for the groundbreaking couturier. Inspired initially by Marie de Noailles and perhaps a little by the apartment of “Coco” Gabrielle Chanel, their apartment developed a personality of its own, glorying in its own self-conscious brilliance. The combination of old master paintings, with a Warhol portrait of their dog Moujik cohabiting happily with seventeenth century reliquaries, was groundbreaking. This juxtaposition embraced the triumphs of modernity in the form of Eileen Grey and Mondrian and supported them with objects with serious historical gravitas.

Butler Adil Debdoubi adjusts the Jacques Grange–designed curtains in Saint Laurent’s grand salon. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

Saint Laurent’s collector’s euphoria overflowed into his own oeuvre; between 1979 and 1981, the couple’s peak collecting years, Saint Laurent produced a dazzling series of embroidered, beaded, and appliquéd evening dresses, exuberantly paying homage to Picasso, Matisse, and Léger.

A Mondrian dress at YSL’s retrospective, final haute couture show in 2002 at Paris’s Pompidou Center. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier.

A pair of undulating lily-motif mirrors, crafted in bronze and copper by Claude Lalanne for the upstairs music room, led, between 1974 and 1985, to the proliferation of over a dozen more, floor to ceiling. “I can’t live in a room without mirrors,” Saint Laurent said. “If there aren’t any, the room is dead.” The effect in the music room of their multiplying reflections was vertiginous—a touch of Mad Ludwig of Bavaria, as seen through the lens of Luchino Visconti. “Some nights it’s a little unsettling,” Saint Laurent admitted.

The red hues of the music room evoke the designer’s native Algeria. “Color is a reflection of the soul,” he once noted. Lacquered fish are behind a Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann low table and piano displaying Dunand vases. The lamp is by Armand Albert Rateau. Photography by Pascal Hinous, Marianne Haas

“After all, decorating an apartment, house, workshop, or even office, generally means executing a portrait of its occupant. An interior that is totally successful reveals the character, roots, profession and hidden desires of a person with far more accuracy than handwriting analysis or an astrological horoscope.” – Pierre Passebon, author of Jacques Grange Interiors. True to Passebon’s ideas of seeing a person’s personality through their decorative scheme, the differing personalities of Saint Laurent and Bergé become increasingly clear as their relationship continued. This is expressed in their interior style almost as much as they fight and yet desperate need to stay together in the film.

Pierre Bergé is classical, his choice of style emanates tradition and classical power where as the taste of Saint Laurent is often based on narrative fantasy. Saint Laurent is a different character in every home. In his bachelor apartment he interested in tribal art, reflected in a simple, clear tonality. In Château Gabriel, their shared country retreat near Deauville, he is a character from Proust in a Belle Epoque world that is claustrophobically cushioned and cluttered. In the fabulous datcha conceived there as a little folly and an escape from the big house, he is perhaps a White Russian or a Cossack. One can only imagine how much the design of this room influenced his wonderful Russian Ballet collection. In his workroom he is a scientist sporting a white coat with modern minimalism. In his office he is a maître couturier in a gilt-and-eau-de-Nil universe. Not surprising, considering his childhood in Algeria, it is perhaps in Morocco where he is most of all at home with colour and light.

A small nook in the library at Villa Marjorelle, which Yves Saint Laurent said was his ‘favorite room in the world.’ Courtesy The Wall Street Journal Magazine. Photography by Oberto Gili.

Bergé is more consistent in his interior style – although significantly he did not employ Grange in his own apartment in Rue Bonaparte – and the same themes always return, power, classicism, knowledge, ownership and appropriation.

It is impossible to talk about Jacques Grange without discussing the work that he did for Yves Saint Laurent but this work does not define Grange; he is a little more elusive than that. The work is never about him but always returns to the client. A charming projection of their taste, choice and perhaps most importantly aspiration which is then passed through Grange’s prism and emerges splendid, light, harmonious and perhaps a little more inspired and beautiful than at the outset.

Choosing paintings together was “one of the strongest dialogues between Pierre and Yves,” Madison Cox says, “the discussion, the chase, the passion.” In spite of lovers’ quarrels, indiscretions, and, eventually, separation (in 1992, Bergé took an apartment on the Rue Bonaparte) “they remained united through the collection.”